By Brother Richard Piper, Hecker Camp Treasurer

These days, America’s enemies, as in decades and centuries past, are saber rattling. How does our country prepare?

Some say the U.S. military has become weak because of social trends like “wokeism” or individuals being discharged for not getting COVID vaccines. But the fact remains, we are facing a manpower crisis with these world pressures.

The U.S. has a population of more than 300 million people. Though, all branches are struggling with recruiting. Only 23% of Americans 17-24 are qualified to serve in the military without a waiver due to obesity, criminal records, physical problems, drug use, lack of a high school diploma or an inability to pass literacy and math tests. Only 9% of those young Americans eligible to serve in the military had any inclination to do so. This is the lowest number since 2007, according to an internal Defense Department survey.

The U.S. Army is 20,000 people short of its recruiting goal for fiscal year 2022. The revival of the military draft is not imminent, but 2022 is the year we question the sustainability of the all-volunteer force.

The military draft ended in 1973, so I wonder how many were draftees like I was? I tried to join the Air Force when I was 18, but I was denied because of two leg operations. Then, I was drafted by the Army when I was 22 in 1972. I joined for an extra year for the choice of job duty and location of service.

The Civil War Draft

Let’s look at those who served during the Civil War. The U.S. had a population of more than 31 million at the start of the war. Three million men bore arms during the Civil War. This breaks down to about three Union troops to every Confederate or about 10% of the population.

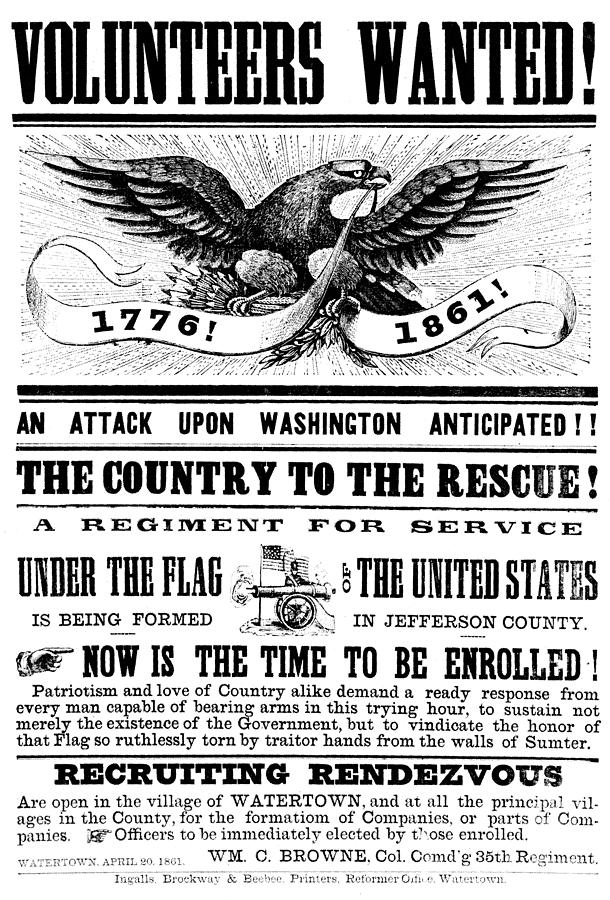

Both the North and South surged into war with armies of volunteers committed to fight. By April 1862, volunteers were not enough to fuel the rebel cause, and the first American conscription began.

On March 3, 1863, President Lincoln signed the act that required all men between 18 and 45 be enrolled into the local militia units for possible call to Federal service. Telegraph operators, judges and government employees were exempted. Also excluded were men with mental or physical disabilities such as being blind in the right eye, missing fingers, as well as men missing front teeth and molars because they would be unable to bite open the paper cartridges of the day.

Conscription in the Union Army began the summer of 1863. Every able-bodied white man between 18-35 was subject to the draft.

Drafting was done by individual states. Each state had a quota based on its population. Volunteers were deducted from the overall quota, and the number left of the quota were drafted. However, the largest number in both armies were still volunteers.

More than 98% of the enlisted men were between the ages of 18 and 46 years old. Most were native born Americans.

Of the Northern Armies, about 25% were mechanics, and almost 50% were farmers. The rest were laborers, 16%; business and salespeople, 5%; professionals, 3%; with the rest coming from other parts of the population.

Two farmers in my family served and sacrificed their lives for the Union. William H. Piper enlisted at age 25 on Oct. 13, 1862. He served in the 93rd Illinois Infantry Regiment, Company B. John C. Piper enlisted at age 23 on the same day and in the same regiment and company. William died two months later in Holly Springs, Mississippi from lung fever or Ballious fever. John mustered out after five months, disabled and with heart problems. He would die a little more than a year later in April 1864 at age 25.

More southerners were involved in agriculture. Nationally, less than 12% had any involvement with individuals or businesses connected to slavery. In the south, 75% of the white population had no interest in or connection to slavery. Just about 10,000 American families made up the bulk of the nation’s slaveholders. More than 38% of all southerners were held in slavery and outnumbered whites in Mississippi and South Carolina.

Draft Opposition

The draft was widely unpopular. The first major draft disturbance of the civil war happened Nov. 10, 1862, in Port Washington, Wisconsin. An unruly mob chanted, “No draft! No draft!” The crowd included many immigrants who opposed the war, the draft and compulsory military service. A full-blown riot broke out, and state commissioner William A. Pors is pushed down the courthouse stairs, pummeled, kicked, pelted with rocks and flees for his life. Others went west into the territories out of the reach of the draft agents.

By 1864, the Confederacy is desperate for manpower and votes to extend the draft age to include those 17 to 50 years old, as well as free blacks and slaves for auxiliary service. In the north, because conscription was so hated, local jurisdictions offered bounty money to entice men to volunteer. Soon, legions of “bounty jumpers” were enlisting in one jurisdiction, only to desert and then join up in another collecting bounty money.

A commutation clause in draft laws of both north and south allowed men who could afford it to pay $300 instead of enlisting, or to hire a substitute.

Confederate men owning or overseeing 20 or more slaves were exempt from service, leading to cries of “rich man’s war, poor man’s fight” as wealthy men could not be forced into the army, but poor men could.

To avoid the draft and meet their quotas, some local communities offered bounties to enlistees as high as $700. The price of an 80-acre frontier farm at the time was about $300. In 1862, $300 was close to a year’s income for an unskilled laborer. Even a skilled mechanic would not make twice that much money in a year, and in the course of things, never saw actually as much as $300 in cash.

About, 75,000 men were hired by the drafted civilians as substitutes, with about 6% of the total strength of the Union Army being draftees.

Foreigners, especially the German and Irish communities, opposed the draft and renounced their intent to become citizens. Some got “Canadian Fever” and fled north.

New York City

New York City was a strange city during the war. For many years, its merchants had strong commercial ties to the South. It was the trade rival of Boston, Massachusetts and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and was the money capital of the nation. It was also a corrupt city. Most did not care who won the war so long as they profited from it.

In 1861, when Fernando Wood was mayor, he had proposed that New York City and Long Island secede from the U.S. and become a free port to trade with both sides.

In 1863, Manhattan Island had a population of 813,669; of these, more than 200,000 were Irish who had come to the city after the potato famine of 1848. As the most recent arrivals, these half-starved and desperate people had to contend with blacks for the bottom jobs. There were 120,000 Germans and 50,000 people from other countries. The Irish had no interest in a war whose results might ruin them.

When a second draft drawing was held on July 13, 1863, Irish workers appeared en masse. Soon, a mob of 50,000 burned, looted and pillaged the city. The mob also

contained native born who were very poor with nothing to lose. Anti-black feeling in New York also fanned the flames of the draft riots. The violence included arson, beatings, shootings and hangings that lasted for three days.

In the end, 2,000 people were injured, 120 killed; including at least two women and eight black people lynched. Fifty buildings were burned to the ground. The riots only ended when President Lincoln sent in large numbers of Union soldiers to put them down.

In Summary

It takes a tough military to keep a country strong and protected. Whether we continue with an all-volunteer force or see a revival of the draft remains to be seen. The country needs to see changes to have a more favorable view of the

military and those who serve in it.