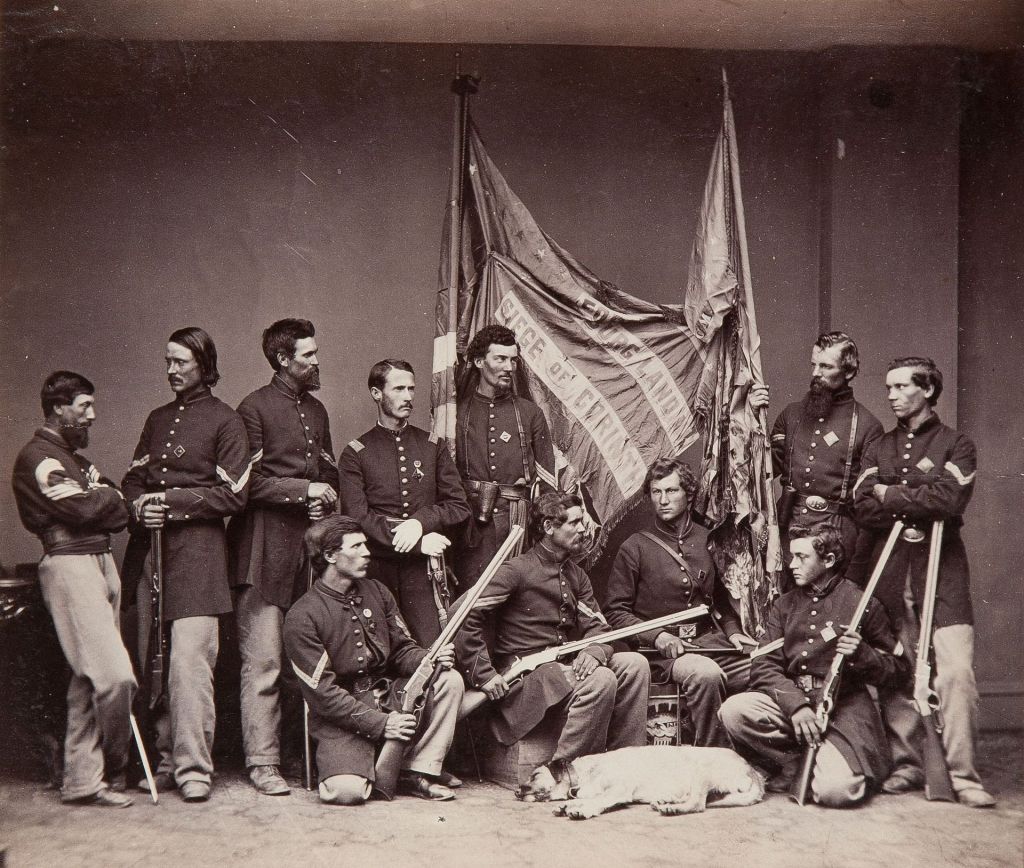

Color bearers of the 71st Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry armed with Henry rifles.

(Courtesy photo)

By Brother Richard Piper, Treasurer

Col. Frederich K. Hecker Camp #443

When viewing civil war art, the U.S. Flag dominates sketches and drawings because it played a special and vital role in the war. In today’s world where flag desecration can be viewed as one’s right to free speech, the civil war soldiers in the Union held a much different view.

George F. Roote wrote, “The Battle Cry of Freedom,” which was one of the top three favorite songs among Union troops. “Yes, we’ll rally round the flag, boys, we’ll rally once again, shouting the battle cry of freedom,” was a song my classmates sang in the late 1950s and early 1960s in grade school. I can see why it was a favorite.

After Maj. Edward Pye of the 6th Wisconsin Regiment gave the order, “Charge!,” no other commands were given except, “Align on the colors! Close up on that color! Close up on that color!”

A regiment’s flag was its pride and glory. When seen within enemy lines or planted there, it showed victory. A bobbing flag going forward showed the speed of an attack. If the flag stopped, fell back or went down, it was a sign of chaos or trouble for the unit.

On July 1, 1863, on the first day of Gettysburg, nine color bearers carrying the regimental flag of the 24th Michigan Regiment were killed carrying the flag. The 26th North Carolina Regiment saw 14 of their color bearers shot down.

The Color Guard

The Color Guard The color bearer was protected by a color guard comprised of a sergeant and five to eight corporals. The color guard went into battle at “shoulder arms,” but then went into action when the battle started. Situated in the center of the battle line, it marked the spot of receiving the hottest fire from the enemy, usually resulting in the death of the color bearer who was unarmed. Typically, with the sergeant and corporals’ death rates coming next.

During the Mexican War, young lieutenants in many regiments served as color bearers, just for the honor. At the Battle of Chapultapec, Lt. James Longstreet was shot carrying the colors. He handed his flag over to another lieutenant by the name of George E. Pickett.

In the Civil War, many officers on both sides led charges with regimental colors, including George Armstrong Custer.

Rebelling Against the Flag

When Federal forces first entered Virginia on May 24, 1861, a flag incident caused the first death there. Tavern owner James T. Jackson was flying a Confederate flag from his roof. Col. Elmer Ellsworth, of the 11th New York Regiment Fire Zouaves, saw the flag on the roof where he went and took the flag down. On his way back down the stairs, Jackson shot and killed Col. Ellsworth, whose body was taken to the White House. Mrs. Lincoln was offered the bloodstained Confederate flag, but she covered her eyes and did not want the flag.

In April 1862, New Orleans fell to Union troops. Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler took command of New Orleans. He decreed that he would not tolerate any activity or gesture that supported the Confederacy.

Professional gambler William B. Mumford tested the edict by going to the U.S. mint and chopped the American flag staff in two. Butler had him arrested, tried by a military tribunal and hanged at the site of his crime.

A woman made a dress from a Confederate flag and flaunted wearing it in public. General Butler again expressed his disgust by having her seized and then deported to Fort Massachusetts on the barrier island known as Ship Island for two years.

Respect for the Flag

Respect for the flag was taught to the children. In Akron, Ohio, a Sunday School teacher told the children to stand and recite their favorite Bible verse. An 11-year-old boy stood up and said, “If any one attempts to haul down the American Flag, shoot him on the spot!”

When the flag was no longer flying, it usually meant defeat or surrender. As long as it flew, the flag meant “no surrender.”

When the USS Cumberland was sunk by the CSS Virginia (formerly the USS Merrimac) at Hampton Roads, Virginia, it sank with the American Flag still flying at her peak, signalling it had not surrendered, but was fighting until its watery end.

When Maj. Robert Anderson surrendered Fort Sumter, South Carolina, he was granted his terms to fire a salute of 100 guns before lowering the U.S. Flag. At the half-way point, the salute had to end when gunpowder exploded and killed a soldier making him the first to die in the war.

In late 1867, a former Union sergeant, Gilbert Bates of the Wisconsin Heavy Artillery, disagreed with a fellow Veteran who said the South hated the Union flag. To prove his theory, the 39-year-old Union Veteran went by train to Vicksburg. Once there, he unfurled an American Flag and started his walk to Washington, D.C. In Montgomery, Alabama, the first rebel capital, citizens en masse turned out to cheer him. In South Carolina, where he followed Sherman’s march, he was not assaulted or threatened. At the border of North and South Carolina he was met by an honor guard of 25 Confederate Veterans. After a walk of three months, he reached Washington, D.C., on April 14; the anniversary of the firing on Ft. Sumter. His walk was seen as showing sectional hatred was dying.

Post Reconstruction

Once reconstruction ended, Confederate Veterans began to press for captured rebel flags to be returned. Congress denied measures to return flags to states several times. President William McKinley, an Ohio Civil War Veteran, took the initiative to have flags returned, stating, “decency and honor required this gesture of courtesy.” By 1910, most Federal agencies and institutions had returned Confederate flags, but some states refused to do so.

About 30 years ago, I wrote to my senator to express my desire for an amendment to protect the flag. I was told that it could not be done because other citizens would lose their freedom of speech.

As for me:

Yes we’ll rally ‘round the flag, boys

We’ll rally ‘round again

Shouting the battle cry of freedom

We will rally from the hillside

We’ll gather from the plain

Shouting the battle cry of freedom

The Union forever, hurrah boys, hurrah

Down with the traitor, up with the star

While we rally ‘round the flag, boys

Rally once again

Shouting the battle cry of freedom

We will welcome to our numbers

The loyal, true and brave

Shouting the battle cry of freedom

And although he may be poor

Not a man shall be a slave

Shouting the battle cry of freedom.

Fort Massachusetts on Ship Island, where a woman was imprisoned for disrespecting the U.S. Flag. (Courtesy photo)

Leave a comment