By Brother Richard Piper

Hecker Camp #443 Treasurer

Compared to Europe, the United States was a medical backwater as no license or medical degree was required to practice medicine, and many doctors had neither. Instead, many learned the trade as apprentices to older doctors. A degree was no guarantee that a doctor was well trained either.

Medical schools, on average, consisted of two, four-month terms in a two-year period. First and second year students attended the same lectures. There was no clinical work and no surgical demonstrations. Attendance was not required, and exams were minimal. Harvard did not have microscopes in lab work until 1871.

Doctors relied on emetics (any agent that produces nausea and vomiting), purgatives (laxatives), bloodletting and the pain killing properties of whiskey, which they gave to patients in the absence of anesthesia. Opiates were widespread and legal. During the war, about 95% of surgeries were performed under anesthesia using ether or Chloroform.

Hospitals

The Union Hotel Hospital was infamous for it’s poor conditions. (Photo courtesy of National Archives)

Hospitals were charity institutions and typically existed only in the largest cities like New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. Doctors in smaller towns would not have practiced at a hospital in most cases. Even in large cities, female family members attended the ill at home, perhaps with a visit by a doctor. If surgery was necessary, it was typically performed by the doctor on the kitchen table, and only the poor and desperate went to a hospital when they were ill.

Some diseases were known as “hospital diseases” since the same bed linen would be used for several patients. The hospitals smelled so bad that the hospital nurses used dry snuff.

When the 6th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment arrived in Washington D.C. on April 19, 1861, after some were injured during the riots in Baltimore, Maryland, they had nowhere to go. The Quartermaster Corps, an independent department of the army, had refused to build hospitals in anticipation of the pending war.

“Men need guns, not beds,” and the 6th Massachusetts, both injured and uninjured, slept on the carpeted floor of the Senate chambers that night. By June 1861, 30% of the army was on sick call due to infectious diseases; most notably typhoid and dysentery, which are both associated with poor sanitation.

To cope with the crisis, the Medical Bureau requisitioned buildings in the Washington D.C. area, like hotels and schools for use as general hospitals. Many were run down with poor ventilation and poor toilet facilities which caused more problems. Many latrines were too close to the water supply and kitchen, so Flies from the latrines spread their germs to the water and food preparation areas and food bowls.

The largest Washington D.C. hospital was the Union Hotel opened on May 25, 1861. It was infamous for poor conditions and worse smells, and there was no dead house to place bodies. It closed a year later, then reopened in July 1862 for the wounded from the Seven Days Battle. It closed for the last time in March 1863.

At the start of the war, the Union Medical Bureau had thirty surgeons and eighty-six assistant surgeons. Twenty-four resigned and joined the Confederacy. Three more were dismissed for disloyalty. These surgeons were not experienced. Of the 11,000 Union surgeons, just five hundred had surgical experience, and of 3,000 Confederate surgeons, just twenty-seven had surgical

experience.

Bull Run

Civilians and soldiers turned surgeons were amputating and binding up the limbs of the wounded from the Bull Run Battlefield. More than 1,000 men were left on the battlefield, while some bloodied and often shoeless soldiers walked the twenty-five miles back to Washington in search of aid. A cold rain fell for two days afterward, while two-wheeled ambulances, nicknamed “the avalanche” by the sick and wounded, traveled in them. Before the battle, they had only been field tested as a carriage for officer pleasure jaunts and as light trucks by the Quartermaster Corps. They had not been field tested as ambulances.

Surgeon General Clement Finley designed them before his promotion to surgeon general. Flimsily constructed of light-weight wood, they were prone to breakdown and were painful for the wounded who screamed and begged to be let out.

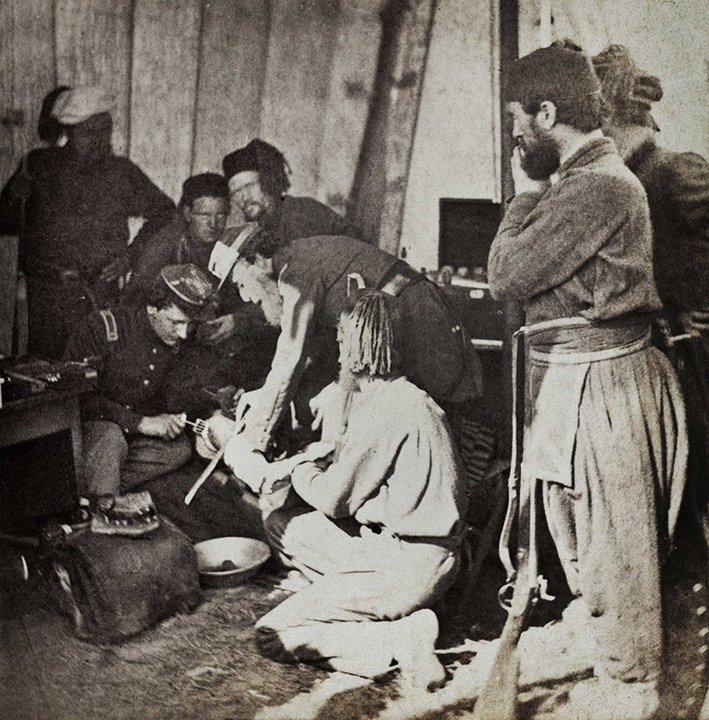

(Left) A nurse prepares to spoon-feed

soldiers in this photograph taken inside a Union hospital. Women also likely donated the coverlets warming the men. (U.S.A.M.H.I., Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, Photo by Jim Enos)

The six military hospitals created in and around the capital in the months before Bull Run were already overcrowded with dysentery patients when the battle began. The army requisitioned churches, temples, the top floor of the U.S. Patent Office, St. Elizabeth’s Insane Asylum, hundreds of private homes and even the capitol building.

Soldiers laid in the streets in large numbers on the bare ground. Men spent the night in ambulances going from hospital to hospital looking for a vacancy. To make room, men were released from the hospital with no way to get back to their regiments, and nowhere to stay in the city.

In the ward set up in an unfinished storage room on the top floor of the patent office in Washington, the wounded and ill lay in groups of six on crude tables built from pieces of construction scaffolding. A system of pulleys carried barrels of water, baskets of vegetables and sides of beef up the marble face of the building and through a top floor window. Mansion House Hospital was the largest of the army’s 14 general hospitals in Alexandria, Virginia with 516 beds and a library and organ on the first floor where church services were held.

More about Civil War nursing and medical care will be coming soon.

References:

Faust, Drew Gilpin, (2008). The Republic of Suffering-Death and the American Civil War. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Toler, Pamela D. PhD., (2016). Heroines of Mercy Street- The Real Nurses of the Civil War. Back Bay Books, Little, Brown and Company, New York, Boston, London.

Leave a comment