By Brother Richard Piper

Hecker Camp #443 Treasurer

At the start of the Civil War, the primary source of trained nurses in the U.S. were the nuns who staffed 28 Catholic hospitals in the U.S., several of whom served in army hospitals during the war.

There were no nursing schools in the U.S., though there were at least two in Europe. Kaiserwerth, Germany where Florence Nightingale trained, and Nightingale’s own school in St. Thomas Hospital in London, England that opened in 1860.

In the early months of the war new nurses paid their own expenses and made their own travel arrangements. By 1862, the government was required to provide travel expenses for nurses working with Dorothea Dix, but getting proper documents was often a challenge.

On Aug. 30 alone after the Second Battle of Bull Run, 400 vehicles of various kinds, nearly 2,000 horses and mules and more than 1,000 drivers and attendants were needed to recover the wounded from the battlefield.

Binding Wounds

Clara Barton was an educator and nurse who assisted soldiers during the American Civil War. Barton served as an independent nurse and first saw combat in Fredericksburg, Virginia, in 1862. She also cared for soldiers wounded at Antietam in Maryland. Barton was nicknamed “the angel of the battlefield” for her work. She became the founder of the American Red Cross in 1881. (Photo courtesy of National Archives)

The most obvious skill nurses needed to learn, and the one they took the most pride in mastering was how to dress and bandage a wound.

For a wound to heal, dead and infected matter had to be removed; a process that would be undertaken with surgical tools, topical disinfectants like bromine, iodine or common vinegar. In some cases, dressings needed to be changed several times a day.

Roughly 94% of the wounds were caused by minie balls that flattered when they met human flesh tearing thru muscle and bone. When hit, bones would splinter and shatter into hundreds of spicules or bony shreds that drove thru muscle and skin. Bullets usually lodged in the body that almost always left an infected wound that seldom healed and often led to amputation.

Infectious diseases, including pneumonia, cholera, malaria, dysentery and typhoid accounted for 64% of the deaths among enlisted men in the Union Army. Officer rates were lower due to better food and less crowded living conditions, but were also two times as likely as enlisted men to be killed in action.

Everyday Tasks

Many of the tasks women performed in the hospitals were domestic chores, like feeding patients, making beds, overseeing and sometimes, doing laundry.

Field nurses and those on transport ships often had to cook simply because there was no one else to do it. In the general hospitals, much of the cooking was assigned to untrained convalescent soldiers.

Gastrointenstinal illnesses made it hard for patients to eat the common diet served to active and invalid soldiers alike, which was often heavy, greasy and course. One regimental medical officer described it as, “death from the frying pan.”

In 1864, nurse Annie Turner Wittenmeyer, an Iowa State Sanitary agent, convinced the army to hire experienced women to superintend “special diet” kitchens in the general hospitals; a change that raised both the quality of convalescent food and the status of cooking as a hospital job.

She convinced the U.S. Christian Commission to create special diet kitchens in military hospitals, with herself as the supervising agent.

U.S. Sanitary Commission/Hospital Transport Ships

The army contracted with the U.S. Sanitary Commission to operate a semi-independent hosptial transport system using steamships to evacuate wounded and sick soldiers through the James and Pamunkey Rivers, and then take them up the coast to northern hospitals.

The army quartermaster would provide a fleet of ships to serve as hospital transports. The Sanitary Commission would staff and supply them.

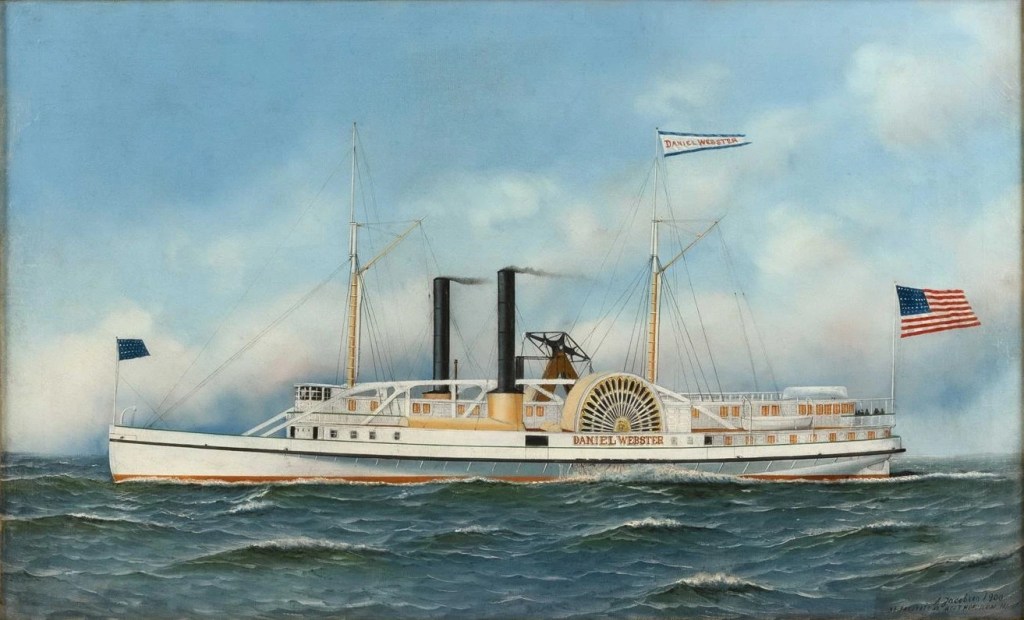

The Hospital Transport Service received its first steam ship, the Daniel Webster on April 25, 1862. Over the coming weeks, the commission converted another 14 ships into floating hospital transports which included three steamers capable of making the ocean passage from Fort Monroe, Virginia to New York, along with the Wilson Small, a shallow draft boat that could navigate creeks and shallow tributaries and would be used to bring both wounded and nurses downriver to the larger transport vessels.

Each ship was staffed by at least one volunteer surgeon, one assistant surgeon, a lady superintendent, a ward master and two nurses for each ward.

Nurse Katherine Wormeley estimated her team recovered, treated and transported almost 4,000 men over a three-day period at the height of the campaign.

Daniel Webster was an American steamboat built in 1853 for passenger service on the coast of Maine. In April 1861, she was chartered by the United States War Department and used as a troop transport. (Painting by Antonio Jacobsen)

Transport Ship Conditions

The Sanitary Commission promised its nurses and their families that transport ship service would be a sheltered experience. However, in reality, the transport ships were closer to the battlefield than their counterparts in the military hospitals and saw some of the worst scenes of suffering of the war.

Nurses often worked for two to three days with little sleep, and snatched meals when the demands of duty allowed. They hauled buckets of water for cooking, cleaning and laundry. They cooked endless gallons of gruel and beef tea over spirit lamps.

Nurses’ clothing changed from ribbon and ruffles to abandon the filthy dresses to a skirt and “Agnews” – a flannel shirt with open collar, sleeves rolled up and skirt tail out – named for the doctor from whom they stole the first shirt.

After May 4, the Sanitary Commission transported thousands of sick and wounded men from the Virginia Peninsula to military hospitals in New York, Philadelphia, Washington, Annapolis and Baltimore. But in mid-July, Confederate gunboats began firing on the Sanitary Commission ships. By the end of July, the Commission had turned the responsibility for transporting casualties back to the Union Army. The hospital transport service was finished, but the war was not.

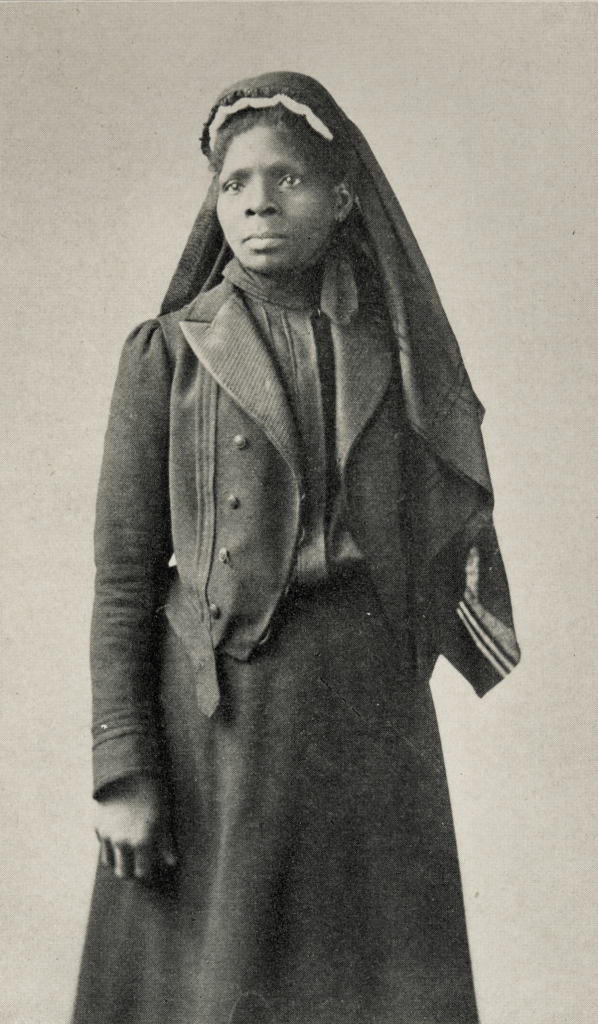

Susie King Taylor was a former slave who gained her freedom as the Union took over Confederate strongholds in the South. Once under the protection of the Union Army, she took an active role by becoming a nurse to wounded soldiers. (Photo courtesy East Carolina University)

Standards of cleanliness required the patients’ undergarments to be changed just once per week and saw nothing wrong with reusing lightly soiled bandages.

Ward floors were dry scoured clean with sand. Some nurses and attendants had to be trained to empty bedpans each time they were used. A patient might need three clean dressings and a shirt daily, which all would need to be thrown away because they were so stained with blood and pus.

The surgeon had to sort out the dead from the dying and the dying from those who might be saved. Amputations required speed to cut tissue, saw the bone and tie off blood vessels in a matter of minutes.

After Gettysburg, it took 300 surgeons five days to perform the necessary amputations. In the Civil War, over 60,000 amputations were performed, and 75% survived, especially if done within 48 hours after the injury.

References:

Faust, Drew Gilpin, (2008). The Republic of Suffering-Death and the American Civil War. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Toler, Pamela D. PhD., (2016). Heroines of Mercy Street- The Real Nurses of the Civil War. Back Bay Books, Little, Brown and Company, New York, Boston, London.

Leave a comment