A photo of what remains of the Alton, Illinois prison. (Courtesy photo)

By Gerald Sonnenberg

Hecker Camp secretary, editor

Imagine suffering sweltering heat or blistering cold, little to eat, filth, disease and the stench of thousands of others in the same situation. This was the environment for most Union and Confederate troops captured during the American Civil War. By the end of the war, there would be more than 150 prisons of various sizes, established both North and South, to hold the nearly half a million Union and Confederate soldiers captured during the war. However, when the war started in April 1861, most of these prison camps did not yet exist.

Earlier prisoner exchanges

The Federal government initially adopted a tough attitude toward Confederate prisoners. The Lincoln administration wanted to avoid any action that might appear as an official recognition of the Confederate government, including the formal transfer of military captives. But in the North, public opinion on prisoner exchanges would soon begin to soften after the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861, when the rebels captured about

one thousand Union soldiers. Petitions from prisoners in the South and editorials

in Northern newspapers eventually brought pressure on the Lincoln administration.

In addition, as opposing forces headed into the field in the summer of 1861, and with no means for dealing with large numbers of captured troops, commanders began negotiating individual exchange agreements on their own.

Both Union and Confederate leaders would typically rely on a traditional European

system of parole and exchange of prisoners. A prisoner who was on parole promised not to fight again until his name was “exchanged” for a similar man on the other side.

Union and Confederate forces exchanged prisoners sporadically, usually as an act of humanity between opposing field commanders. In some cases, a transfer of only sick and wounded captives took place. Exchanges for just a couple of prisoners between sides could prove very time-consuming to achieve. There were also a few military commanders unfamiliar with the practice who were reluctant to engage in exchanges without explicit

approval and instruction from their superiors.

On Dec. 11, 1861, the U.S. Congress passed a joint resolution calling on President Lincoln to “inaugurate systematic measures for the exchange of prisoners in the present rebellion.” During meetings on Feb. 23 and March 1, 1862, Union Maj. Gen. John E. Wool and Confederate Brig. Gen. Howell Cobb met to reach an agreement on prisoner exchanges. However, differences over which side would cover expenses for prisoner transportation stymied the negotiations.

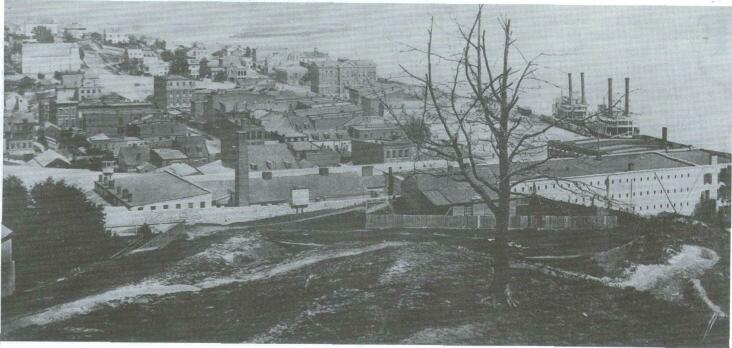

This view of Alton, Illinois in 1862 clearly shows the prison in the foreground as the large

white structure. The building with the multiple windows was the original blockhouse

when the prison was the State Penitentiary before the war. (Photo, national archives)

But Wool and Cobb did discuss many of the provisions later adopted into the Dix-Hill agreement.

Dix-Hill Cartel

Talks continued in the summer, and the Dix–Hill Cartel was signed by Union Maj. Gen. John A. Dix and Confederate Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill at Haxall’s Landing on the James River in Virginia on July 22, 1862. It was the first official system for exchanging prisoners during the American Civil War, and “it was patterned upon a similar arrangement used by the Americans and the British during the War of 1812,” by using a sliding scale to calculate

the relative values of officers and enlisted personnel.

The agreement established a “scale of equivalents for captured officers to be exchanged for fixed numbers of enlisted men, and agents from each side were appointed to conduct the exchanges at particular locations. Prisoners could also be released on parole.”

For example, a navy captain or an army colonel was worth fifteen privates or ordinary sailors, while personnel of equal ranks were exchanged man for man. Each government appointed an overall agent to handle the exchange and parole of prisoners. The cartel also allowed the exchange of non-combatants and civilian employees of the military.

According to the cartel, authorities were to parole any prisoners not formally exchanged within ten days following their capture. The terms of the cartel prohibited paroled prisoners from returning to the military in any capacity including “the performance of field, garrison, police, or guard or constabulary duty.”

Union prison camps lowered the number of Confederates dramatically, often reducing from thousands to a few hundred prisoners. Former Union prisoners were transported

to designated parolee camps. Benton Barracks, a St. Louis fairground that was converted into a Union Army training camp, was designated to receive Union parolees belonging to regiments from Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa and Missouri.

Building prison camps

While prisoner exchanges helped lower the number of incarcerated men, there was still a need for prison camps for the increasing numbers of men captured on the battlefield.

Many were developed from existing buildings such as Salisbury Prison in North Carolina. It was a converted cotton mill in early 1861 and conditions inside were considered quite good at first.

“The 120 or so Union soldiers interned there were fed meager yet adequate rations, sanitation was passable, shielding from the elements was provided, and the prisoners were even allowed to play recreational games such as baseball.”

Locally, the Alton Military Prison north of Belleville, Illinois and across from St. Louis had been the state’s first penitentiary in 1833 before closing in 1857. It reopened in 1862. While it had 256 cells when it closed, it was renovated to house up to 1,750 Confederate prisoners.

Out of the 11,764 rebel prisoners who entered it during the war, more than 1,500 died primarily of diseases like smallpox and rubella. It closed permanently in 1865.

Units like the 144th Illinois Infantry Regiment were created for one-year enlistments just to serve as guards at the prisons. During its service, the 144th lost sixty-nine men to disease while guarding prisoners at Alton.

There were thirty-two major Confederate prisons, with sixteen of them in the Deep South states of Georgia, Alabama and South Carolina. Training camps were often turned into prisons, and new prisons and camps also had to be built.

End of the Cartel

The issue that eventually ended the cartel was that of black soldiers. In July 1862 congress gave the president authority to accept black men into the army. Following the Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect Jan.1, 1863, the government aggressively recruited black soldiers. Nearly 200,000 black soldiers would serve during the war.

Southerners were so outraged by the new Union policy, that on May 1, 1863, the Confederate congress created a joint resolution declaring that captured black soldiers would be turned over to the states and presumably returned to slavery. Their white officers would be “deemed as inciting servile insurrection, and shall, if captured, be put to death or

otherwise punished at the discretion of the court.”

Lt. Col. William Handy Ludlow, the Union’s agent of exchange, reminded his Confederate counterpart, Robert Ould, that color was never mentioned in the agreement. He concluded, “I now give you formal notice that the United States will throw its protection around all its officers and men without regard to color and will promptly retaliate for all cases violating the cartel or the laws and usages of war.”

Ludlow’s threats were soon made into formal Union policy. On May 25 orders went out to all department commanders that no Confederate officers were to be paroled or exchanged.

On July 13, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered that no more prisoners of any rank be delivered to City Point, Virginia for exchange. Ludlow believed this order went too far. When he protested, he was relieved and replaced by Brig. Gen. Sullivan Amory Meredith, who took a hard line in his negotiations with Ould.

Hardline Effect

This hardline effectively ended the exchange of troops, and prisons began filling beyond capacity. General Ulysses Grant was against the exchanges as a military necessity.

He said, “It is hard on our men held in Southern prisons not to exchange them, but it is humanity to those left in the ranks to fight our battles. Every man we hold, when released on parole or otherwise, becomes an active soldier against us at once either directly or indirectly. If we commence a system of exchange which liberates all prisoners taken, we will have to fight on until the whole South is exterminated. If we hold those caught, they

amount to no more than dead men.”

Lack of food and sanitation, the abundance of disease and other issues soon took their toll. Even Salisbury Prison in North Carolina that started with 120 Union prisoners, adequate food and recreation, ended up with a death rate of 28% by October 1864 as its population skyrocketed to more than 10,000.

As victory in the war for the Union became clearer in early 1865, some exchanges began to again take place.

“For thousands of captives, exchange did not come soon enough. At the Confederate prison at Salisbury a burial sergeant recorded 3,406 deaths from October 1864 through January 1865. The toll was also high at the Florence, South Carolina prison. One of the sad ironies of the war is the fact that February 1865, when general exchanges were resumed, was also the month that the number of deaths peaked at the eight largest Union prisons. The toll was 1,646, including 499 at Camp Chase alone.”

Of 194,732 Union soldiers held in Confederate prison camps, about 16% or some 30,000 died while captive. Union forces held about 220,000 Confederate prisoners. Nearly 26,000, or 12% died. These deaths totaled nearly 10% of all fatalities during the war.

While some camps were clearly worse than others, neither North nor South had a clear advantage in acceptable facilities. It is safe to say that all the prisons and camps housing Civil War soldiers were probably overcrowded, unsanitary, with not enough food, blankets, quarters and other necessities. Despite all this set against them, many soldiers did not lose

their will to fight on and live.

A will to live

Private Michael Dougherty, of the 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry, was one of them. At 18, he was captured by Confederates the first time. He was exchanged in May 1863 after a three month stay in Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia. Dougherty was captured again in October 1863, along with 127 others in his regiment, after helping lead a fight for several

hours against rebel forces for which he would later receive the Medal of Honor.

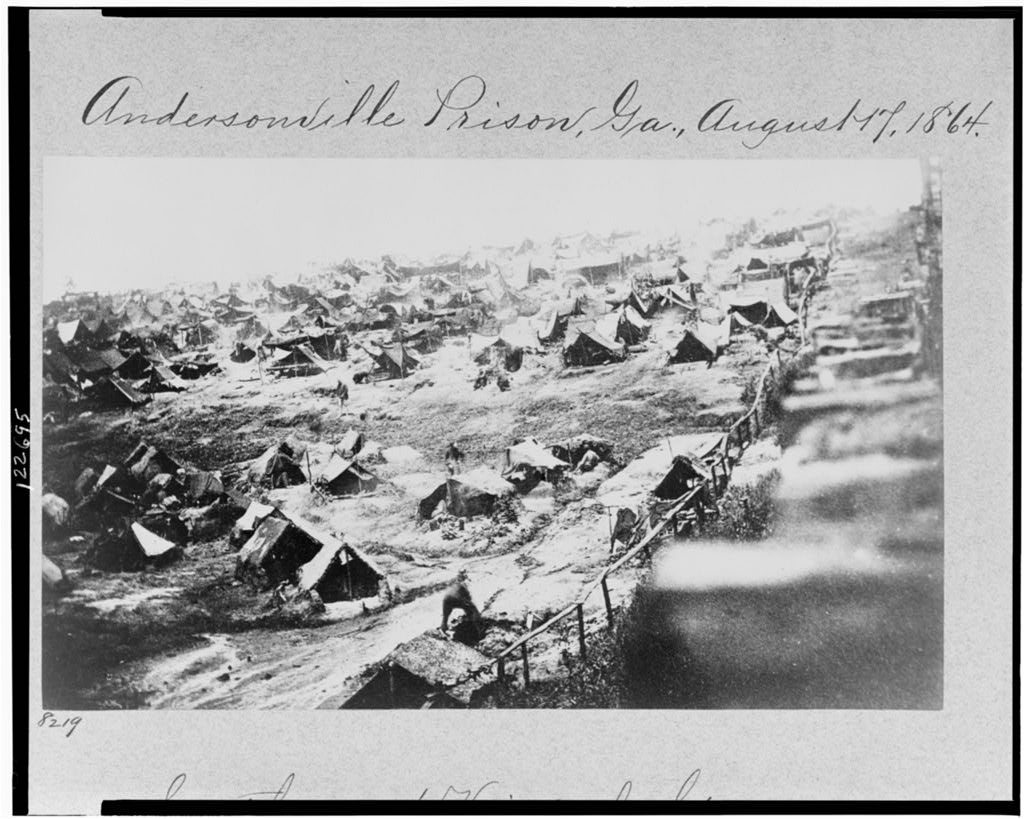

From October to February, he was kept in several prisons in and around Richmond, then boarded a train headed for a new prison near Andersonville, Georgia called Camp Sumter.

He wrote on Nov. 8, 1864, “Election Day in the North for President of the United States. (Captain) Wirz, (commander of the camp) has requested that we have a mock election, and each prisoner is to vote, whether of age or not, and says that whatever will be the majority in the hospital will be a fair test as to the result in the North. We all like McClellan, but

to spite the rebels, most of us will vote for Lincoln. So this afternoon, each man was given two slips of paper with the names of McClellan on one and Lincoln on the other; two rebel sergeants visited each tent with a basket and gathered the vote, and at five o’clock they announced the result, which stood, McClellan 531, and Lincoln 1,239. Wirz is terribly angry and says it will be ‘Link-in and Link-out’ for us for some time to come.”

This meant harder times for the prisoners. It would be hard to imagine worse conditions than what they had already. Regardless, Dougherty would survive his time in the Confederate prison; the only one of his comrades who were captured with him.

After nearly two years in Confederate prisons, he was free and one of the lucky ones. He later married, had twelve children, and died peacefully at home in 1930 at the age of eighty-five having survived the other side of the war.

References:

*Prisoner Exchange and Parole by Roger Pickenpaugh https://www.essentialcivilwarcurriculum.

com/prisoner-exchange-and-parole.html

*144th Illinois Infantry Regiment https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/144th_Illinois_Infantry_Regiment

*James Ford Rhodes (1904). History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850: 1864-1866. Harper & Brothers. pp. 507–8.

*Hesseltine, Civil War Prisons, pp. 9-12.

*American Civil War prison camps https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Civil_War_prison_camps

*Civil War Prison Camps https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/civil-war-prison-camps

*Chambers and Anderson (1999). The Oxford Companion to American Military History. p. 559. ISBN 978-0-19-507198-6.

*Shiels, Damian (2011) Medal of Honor: Private Michael Dougherty, 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry https://irishamericancivilwar.com/2011/03/28/medal-of-honor-private-michael-dougherty-13th-pennsylvania-cavalry/#:~:-text=On%2010th%20December%201864%2C%20Michael%20Dougherty%20made%20the,Michael%20Dougherty%2C%20Co.%20B%2C%2013th%20Pa.%20Volunteer%20Cavalry.

*Dougherty, Michael (1908). Prison Diary of Michael Dougherty, late Co. B, 13th Pa., cavalry, pages 64-65. https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/prison-diary-of-michael-dougherty-1908/

Leave a comment